What Indonesia can teach us about suicide prevention after Covid

Loneliness, financial insecurity, and marginalisation aggravate the risk of self-harm and suicide related to Covid, confirms a new paper from the Southeast Asian country. Are policymakers listening?

Trigger warning

Contains references to suicide and suicidal ideation.

Over three-fourths (77%) of suicides globally occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) — which have been disproportionately hit by the health and economic impact of the pandemic — and yet there isn't enough research on the subject in this part of the world. Earlier this year, researchers from the Southeast Asian country of Indonesia challenged this status quo.

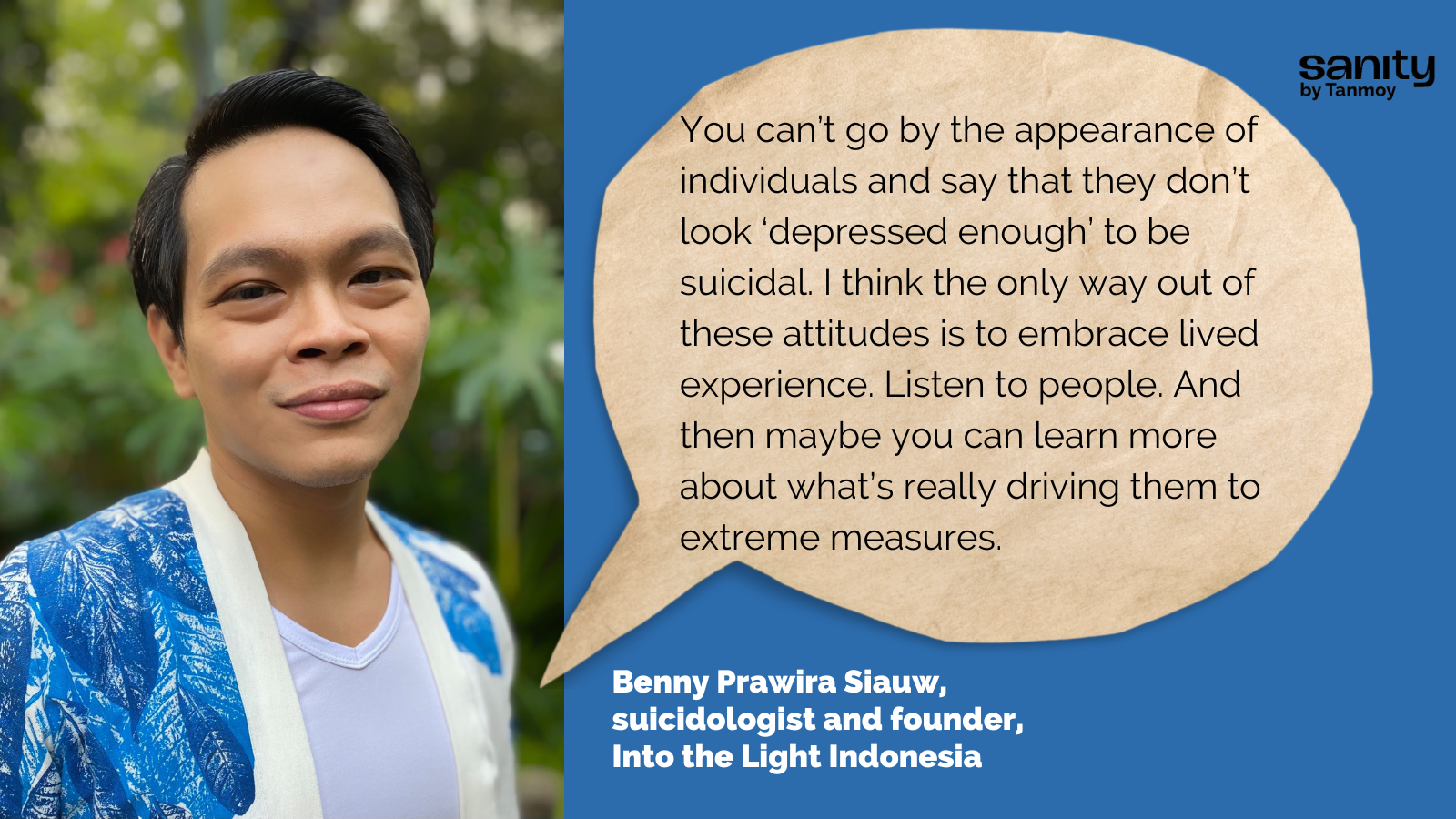

Benny Prawira Siauw is a suicidologist and founder of Into the Light Indonesia, a community-driven suicide prevention movement. Andrian Liem is a research fellow at Monash University Malaysia, specialising in clinical and health psychology. They are coauthors of a new paper* that predicts self-harm and suicide risk among Indonesians as a result of the pandemic. Their work offers fresh evidence of the heightened vulnerability of economically disadvantaged groups and other marginalised populations.

Indonesia does not maintain a national suicide registry, forcing suicide prevention organisations to operate under a debilitating lack of data. Most interventions approach suicide prevention primarily through the lens of reducing stigma, and the absence of data makes it difficult to assess impact.

What lessons does the Indonesian experience hold for other LMICs? Edited experts from an interview:

Tanmoy (T): Let’s start by talking about the background to this paper. What brought you together and why did you decide to research this particular area?

Benny Prawira (BP): Andrian and I have known each other a long time. We have always wanted to research the mental health needs and the huge gaps in access to mental health care among Indonesia’s minority groups. There is hardly any research on minority mental health in Indonesia. We don’t talk about it much because it is a socially and politically sensitive area. We thought the pandemic was the right time for this exercise since mental health in general was being talked about more than ever.

One of the themes we were both interested in was the role of loneliness in suicides.

Through my organisation Into the Light, we’ve been working on reducing suicide stigma. We knew that loneliness is one of the most prevalent risk factors for suicide. Unfortunately the data on this is still dominated by findings based in high-income countries with individualistic cultures. We do not really have much on the more collectivistic cultures, such as in our part of the world.

During the pandemic, people were socially isolated, which gave us an opportunity to explore the impact of loneliness.

Andrian Liem (AL): My background is in research. I was interested in seeing if we could do something concrete with our findings, maybe share them with policymakers and other stakeholders in the mental health care sector. For example, if we could identify the major barriers to accessing health care, perhaps that could lead to some solutions.

T: Could you give me a sense of the suicide situation in Indonesia before and after Covid?

BP: That's a tough question because we do not have any baseline data.

Unfortunately, we do not have a national suicide registry. Every time there is a publication with any reference to suicide rate, it comes from a mathematical model. So they are predicting a number based on some assumptions.

Most published research is confined to a small subset of the population, such as high school students, university students, etc.

T: Yes, the problem of missing data is endemic in vast swathes of the world. In India, we get suicide data from the National Crime Records Bureau. And while there is a lot of underreporting because of stigma, it is helpful to get some numbers. How do you measure progress of any suicide prevention intervention in the absence of data?

BP: Yeah, that's a tricky question. So with any intervention we mostly end up addressing stigma, and we cannot directly assess the impact on the suicide rate. At Into the Light we are focusing on educating people about the risk factors for suicide, decreasing stigma, collaborating with the media to improve public literacy, etc. In our current study, we did have a survey including some indirect questions on self-harm and suicide ideation, but by and large finding reliable data is a big challenge.

T: Often, the experience of LMICs is judged by the quantitative yardsticks of the west, where there is already a culture of data-oriented thinking. It's much easier to collect data, they have the apparatus, they have the infrastructure for quantitative research. But in other parts of the world, it's qualitative data that may be far more easily available compared to quantitative information. Andrian, what kind of limitations does your location pose on you as a researcher?

AL: As you said, researchers in high income countries have far more resources. For example, they can compensate every participant, which is something we cannot afford. Luckily, for our survey we collaborated with a partner whose platform is accessed by many people. But again, it's a limitation because our study is online. We couldn't reach people with limited internet access, those who have no devices. Survey participants here are predominantly young people. So we couldn't get adequate representation from older adults, for example.

T: I remember last year some of us in LMICs were saying look, there is early data coming out of India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Kenya, that show that there is a clear increase in suicides. Now, you obviously can't draw a causal relationship immediately. But it was clear that the pandemic’s economic toll could be severe. In India, for example, there was a spike in suicides among small business owners, whose livelihoods were affected by Covid. Did you also have a directional sense that certain populations in Indonesia could be more vulnerable?

AL: Yes, we did start with some basic assumptions. For instance, that people with less resources and people from the ethnic and religious minority would be impacted more than people with more resources or from the majority.

We also anticipated that people from the LGBTQIA+ spectrum would report higher suicidal ideation than others.

T: Benny, are these trends consistent with what you've seen during your activities on the ground with Into the Light?

BP: Yeah, definitely. This is what I've seen all these years. People from minority groups, people with HIV, people with disabilities, those who come from economically disadvantaged groups — so many of them share the stories [of their struggles] whenever we organise any forum. Covid only made things worse for them. But once again, we do not have the data to say anything conclusively, right? That's the most troublesome thing in this work to be honest.

T: In your paper you point out that the 18 to 24 age group in Indonesia is highly vulnerable to suicide. In India, suicide is the biggest killer in the 15 to 39 age group. What are some of the big stressors that the youth face in Indonesia?

BP: I think a major crisis is the issue of emerging adulthood. You have to assume personal responsibility when you turn from a teenager to an adult, but the way society treats teenagers here is not really helpful.

They are often infantilised, not given the power to follow their heart and voice their needs. Then suddenly, they reach an age when they have to face everything on their own.

Many of them have to move away from their hometown, from their parents, to study in a big city. That gives rise to complex adjustment issues. No wonder people of this age experience so much emotional turmoil.

T: Okay, that is a good segue to my next question. One of the things that the suicide prevention movement has to fight everywhere is this knee-jerk association of every suicide with mental illness. In Indonesia, is there an awareness that suicide is a complex socioeconomic phenomenon? Or do you also see the same tendency to equate suicide with mental illness?

BP: We see the exact same thing here. People tend to put the blame on depression. Whenever they come to me with such a narrative, I ask them, okay, if you say it is the result of depression, then where does that depression come from? Do you think that depression just occurred by itself?

You know, you don't have to be in the DSM category of ‘major depressive disorder’ to have suicidal thoughts. Sometimes there are things in life that make you feel so distressed that you want to escape life. Just because it is too painful to bear.

You can’t go by the appearance of individuals and say that they don’t look ‘depressed enough’ to be suicidal. I think the only way out of these attitudes is to embrace lived experience. Listen to people. And then maybe you can learn more about what’s really driving them to extreme measures.

T: Suicide is not a crime in Indonesia, right?

BP: No, we don't have a history of Victorian lawmaking. But since Indonesia is a very religious country, the stigma around suicide is more likely based on religious belief.

T: Is there a culture of calling helplines etc in Indonesia?

BP: Oh, gosh. Our helpline services completely suck. The government provided a service a few years ago, and then it was shut down. Then they tried to revitalise it, but unfortunately, they said not too many people called and so it was shut down again. Now an NGO has started a suicide hotline mostly used by people in Bali. They also offer help in English because there are many tourists in Bali.

T: What about mental health apps?

BP: Yeah, there are quite a few startups building such apps now. They could be helpful, but when it comes to public innovations like this funded by private, for-profit companies, we need to ask whether they will be equitable. For instance, will they be useful for those who are living in rural areas without even enough electricity? There are also questions about how these businesses treat the mental health professionals who work for them. So yeah, they do bring something new to the table, but they need to take care of the holistic wellbeing of their own staff as well as their clients.

T: I completely agree. They also need to be transparent about the efficacy claims they make as well as their data privacy policies.

BP: Absolutely. For people who are in distress and are looking for [crisis support], these vital issues may not be a matter of priority. Companies must take the responsibility of proactively educating their users.

T: I want to ask you about the role of loneliness, which seems to be a very prominent finding in your study. Was it two years ago that the Surgeon General of the US said loneliness is an epidemic? And I said to myself, I'm sure somebody in the DSM committee is sitting down right now and trying to code loneliness as a new disorder (laughs). I remember there was talk of scientists asking if loneliness could be cured by a pill. In India, loneliness is often associated with the elderly, not so much with young people. What does loneliness look like in Indonesia?

BP: Well loneliness is definitely not a 'disorder', it is a normal human emotion. We want meaningful social connection, and when this need is not fulfilled, of course we feel lonely regardless of how many people are around us. We are so accustomed to thinking that loneliness is only an issue with the elderly, but it is really a universal phenomenon.

T: When you talk to young people, what kind of life experiences do they share that makes them feel so lonely that they contemplate suicide?

BP: I think it is primarily the feeling of being misunderstood. When young people come to me and say that they are lonely, what they are really saying is that they want to be understood by their family. But often, the family becomes the first unhelpful relationship rather than being a safe place. You have to put your family first, but your family does not understand you.

Then of course there are issues in peer groups, when they do not accept you for who you are. You may be judged based on how many followers you have on social media. The socioeconomic gap in the country is another stressor. When people are used to being in an environment where everyone's socioeconomic standard is equal, and then they suddenly find themselves in a different setting with wider gaps, it's often a shock. "Oh my god, I don't understand what you're talking about, I don't understand how to be accepted by you."

So for me, loneliness is the result of not being accepted and understood.

AL: The emergence of new technology, like video calls, has been a blessing but you can shut down this connection by simply closing the screen. Also, you can only see half the body through the camera, you miss out on cues such as body language. The growing feeling of loneliness today is probably because people only have superficial connections, not real human-to-human connections.

T: There's been some research in Indonesia correlating income shock with suicide. A study found that offering cash transfers could lead to as much as an 18% fall in suicides.

BP: Yes, it is quite a big improvement that they reported there. We know that people from the economically disadvantaged group live with suicidal thoughts but lack the resources to access care. Economic interventions could be effective in reducing their vulnerability.

T: What are you hoping for from policymakers who read your paper?

AL: First of all, pay more attention to the communities that are at higher risk.

Sure, suicide is a universal phenomenon, but we cannot deny that certain subgroups are more vulnerable.

Remove barriers to care for young people who may not have enough money to go to health services, for example. Also, remember that these variables or predictors only explain 40% of self-harm and suicidal ideation. So there's still 60% that we don't know much about.

BP: I'd also like to see changes in the insurance system. In Indonesia, if the national health insurer finds out that you tried to harm yourself, your policy will be cancelled and you cannot make any claims. There's a need to revisit this policy so people won't be afraid to seek help. From the perspective of research, we need to urgently get better data, and we must listen more to people with lived experience.

1. Data is a critical weapon in the battle against suicides. The more reliable and granular data we have, the more targeted our social and policy interventions can be.

2. Helping vulnerable young people often begins with making them feel 'accepted and understood'.

3. India is planning a potentially powerful new telemental health programme. We need to lay the groundwork well to make sure that the services are high quality and can be safely accessed by those who most need them. We also cannot delay building regulatory and data privacy frameworks for the burgeoning business of mental health apps.

4. In light of Covid's socioeconomic fallout, we must constantly evaluate risks and design interventions especially for the marginalised and vulnerable communities that have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

*The paper's other coauthors include Selvi Magdalena, Monica Jenifer Siandita, and Joevarian Hudiyana.

PS: I did not independently verify the facts mentioned by the interviewees.

Need help? This website provides contact details of free helplines around the world.

This piece is part of a special series on suicide prevention, supported by Mariwala Health Initiative. Click on the banner below to explore the entire series.