Dying for a paycheque

Like cigarette packets, it's time to put a statutory warning outside offices. "Work kills".

Within a few days last month, work stress at two blue-chip companies in India, EY and HDFC Bank, allegedly took the life of two employees, Anna Sebastian and Sadaf Fatima. In a letter to EY, Anna's mother said that her daughter had been overwhelmed with exhaustion, anxiety, and sleeplessness owing to 'excessive workload' at the Big Four consulting firm that she had joined just four months ago. When Anna brought it up with her manager, she was told, “You can work at night; that's what we all do.” Nobody from the company attended Anna's funeral.

In a leaked letter to employees, EY India's chairman expressed his 'deepest regret' and said that the 'firm places the highest importance on the health and well-being of our people'.

Sadaf died after fainting and falling off her chair at work. Work pressure was implicated in her case as well, according to reports that cited unnamed colleagues. (At the time of writing I couldn't find an official statement from Sadaf's employer. If you've seen one, do share it with me and I will add it in.)

Days after Anna and Sadaf's deaths came World Mental Health Day. This year's theme? Workplace mental health. It's safe to say that despite all the pomp and pageantry, all the webinars and panel discussions on how to fix toxic workplaces, work will continue to kill.

Death is the greatest taboo at the workplace

People dying of overwork and burnout should sear public conscience. But it doesn't, despite all the fleeting outrage that each such death generates. Risking death seems like a fair price to pay if you want to stay employed and get ahead in a turbulent job market. I should know. I've been there and almost didn't return.

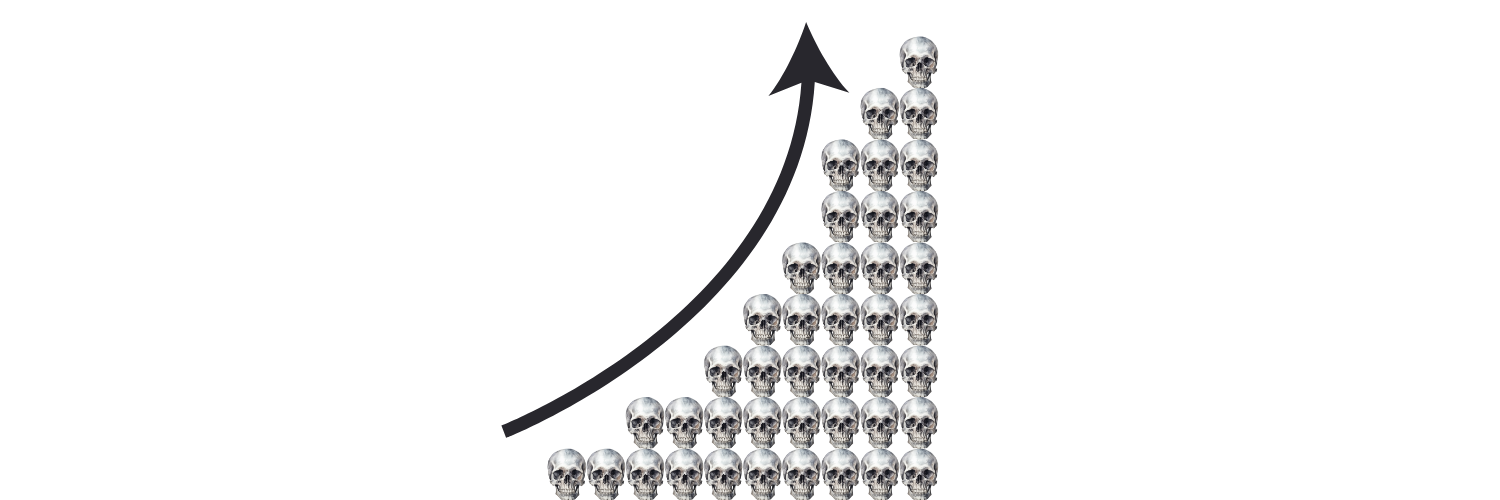

Last year, the International Labour Organization estimated that nearly three million workers die every year due to work-related accidents and diseases, an increase of more than 5% compared to 2015. In his 2018 book Dying for a Pay Check, Stanford b-school professor Jeffrey Pfeffer wrote that in the US alone, workplace environment contributed to 120,000 excess deaths each year, making workplaces the fifth leading cause of fatalities. Differential exposure to harmful work environments, largely a function of people's education levels, accounted for 10%-38% of the growing inequality in life spans.

You cannot begin to fix this crisis without first addressing it with honesty. Instead, notwithstanding the hundreds of millions spent in wellbeing washing and mea culpa statements after one more employee drops dead, employers largely tend to be in denial of their own murderousness.